“I'd like people to remember me for a diligent expert workman. I think a poet is a workman. I think Shakespeare was a workman. And God's a workman. I don't think there's anything better than a workman.”

Picture Legend

1. Ralph Richardson

2. “Hamlet”

3. Roberto Benigni

4. With Vivian in Australia in 1948

5. With Jennifer Jones in “Carrie”

6. “Richard III”

7. With Marilyn Monroe in “The Prince and the Showgirl”

8. With future wife Joan Plowright in the stage production of “The Entertainer,” playing Larry’s daughter

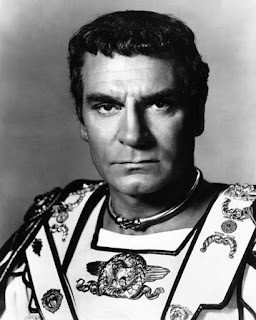

9. As General Marcus Licinius Crassus in “Spartacus”

10. With Stanley Kubrick and Tony Curtis on the set

11. In 1960‘s film version of “The Entertainer”

12. Hollywood Walk of Fame Star

13. With Sarah Miles in “Term of Trial”

14. With Charlton Heston in “Khartoum”

15. With Anthony Quinn in “The Shoes of the Fisherman”

16. Fourth grader

17. With Michael Caine in “Sleuth”

18. “Long Day's Journey into Night”

19. With Katharine Hepburn in “Love Among the Ruins”

20. “Is it safe?” “Marathon Man”

21. As Professor Moriarty in “The Seven Percent Solution”

22. Working for Polaroid

23. “The Boys from Brazil”

24. Larry, Thelonious Bernard, and Diane Lane in “A little Romance”

25. With Donald Pleasence in “Dracula”

26. His last role in “War Requiem”

27. Resurrected for “Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow”

Throughout World War II theatrical director Tyrone Guthrie tried to keep the Old Vic theater going, even after it was left a near ruin due to the Germans being obstreperous and dropping bombs on it in 1942.

After Germany began retreating in Europe in 1944 he thought it was time to reestablish the company in London, and asked Ralph Richardson to lead it.

Ralph wanted to share the management duties with two other people, and Larry and stage director John Burrell agreed to help out.

They were both still in the service though and Old Vic governors approached the Royal Navy and received some special dispensation for them to get released early. Larry thought the RN might have been a little too eager to give him up, as they discharged him with "a speediness and lack of reluctance which was positively hurtful."

They managed to lease the New Theatre for their first season and got some actors together. It was agreed to open with a repertory of four plays: Henrik Ibsen’s “Peer Gynt (as a matter of full disclosure I once performed in a high school production of “Enemy of the People.” I was one of the people),” George Bernard Shaw’s comedy “Arms and the Man,” “Richard III,” by Billy Boy Shakespeare, and and Anton Chekhov’s “Uncle Vanya.”

Larry played the parts of the Button Moulder, Sergius, Richard and Astrov; Ralph played Peer, Bluntschli, Richmond and Vanya.

The first season went pretty well.

The next year they took the show on the road. The company toured Germany, where they were seen by several thousands of Allied servicemen.

They also appeared at the Comédie-Française theatre in Paris, the first foreign company to be given that honor. The critic Harold Hobson wrote that Ralph and Larry "made the Old Vic the most famous theatre in the Anglo-Saxon world (The Anglo-Saxons were a people who inhabited Great Britain from the 5th century. They included people from Germanic tribes who migrated to the island from continental Europe, and their descendants; as well as indigenous British groups who adopted some aspects of Anglo-Saxon culture and language)."

Larry wrote in his autobiography, "Confessions of an Actor," that sometime after the war, Vivian announced calmly that she was no longer in love with him, but loved him like a brother. He was emotionally devastated, but what he didn’t know at the time was that Vivian’s declaration, and her subsequent affairs with multiple partners, was a symptom of the bipolar disorder that eventually disrupted her life and career. Vivian had every intention of remaining married to Larry, but was no longer interested in him romantically.

Still, at some point after their divorce she was quoted as saying, she "would rather have lived a short life with Larry than face a long one without him."

Laurence himself began having affairs (including one with Claire Bloom of “The Haunting” fame, in the 1950s, according to Claire’s own autobiography. Larry played Claire's husband in both Richard III (1955) and Clash of the Titans (1981)).

Larry continued his relationship with the Old Vic company throughout the third 1946-1947 season. He did such a good job that he was knighted in 1947 (as Ralph was six months before Larry). Now he was Sir Larry.

In January of that year Laurence began work directing his second film, “Hamlet,” which was based on a play by Billy Boy, and premiered in 1948. He played the lead role, some Danish prince I believe.

The film became a critical and box office success in Britain and abroad. I just saw it again on Larry’s birthday during the Turner Classic Movie channels tribute to him, as well as some of his other films, and to tell you the truth, I didn’t care for it all that much, but what the hell do I know? Obviously not much as “Hamlet” became the first non-American film (foreign) to win the Academy Award for Best Picture, while Larry won the Award for Best Actor. “Hamlet” is still, to date, the only film of a Shakespeare play to win the Oscar for Best Picture, and the only one to actually win an Oscar for acting. Many have tried but only one... Laurence Olivier, has succeeded.

Larry, and Italian film maker Roberto Benigni (“It’s a beautiful Life”) are the only two actors to have directed themselves in Oscar-winning performances, which apparently isn’t as easy as it sounds.

In 1948 he led the Old Vic company on a six-month tour of Australia and New Zealand. He played Richard III, Sir Peter Teazle in Richard Brinsley Sheridan's “The School for Scandal,” and Antrobus in my favorite playwright’s (Thornton Wilder) “The Skin of Our Teeth,” appearing with Vivian in the latter two plays.

Later he would say that he "lost Vivien" in Australia, a reference to Vivian’s affair with the Australian actor Peter Finch, of “I’m mad as hell, and I’m not going to take it anymore,” fame, whom the couple met during the tour.

Interestingly enough, back in England, after Finch moved to London, Larry auditioned him and put him under a long-term contract with his production company, which allowed Finch’s and Vivian’s affair to continue for many years (some say that Larry subconsciously or consciously might have been grateful for Finch's attentions to his wife, as he occupied Viv’s hours and kept her out of worse trouble).

Working with British theatre manager and producer Binkie Beaumont, Larry staged the English premiere of Tennessee Williams's “A Streetcar Named Desire,” a very controversial play at the time, with Vivian in the central role of Blanche DuBois. The play was panned by most critics, but made a lot of money, and led to Viv’s being cast as Blanche in Elia Kazan’s 1951 film version, with Marlon Brando.

Her good friend, John Gielgud, was troubled that Larry cast her in the part of the mentally unstable heroine: "[Blanche] was so very like her, in a way. It must have been a most dreadful strain to do it night after night. She would be shaking and white and quite distraught at the end of it."

While Vivian was filming Streetcar, Larry joined her in Hollywood to film “Carrie,” based on the controversial novel “Sister Carrie,” and directed by Billie Wyler. The film concerned a young, abused and timid 17-year-old girl who discovers she has telekinesis, and gets pushed to the limit on the night of her school's prom by a humiliating prank. Co-starring with the lovely and talented Jennifer Jones, Larry said he modeled the accent for his character of George Hurstwood, on Spencer Tracy.

He received warm reviews and a BAFTA nomination for his work. Here’s a clip.

Larry and Vivian were popular in Hollywood, with Vivian’s director and co-star stating that they liked Larry very much. Brando liked him so much he didn’t try to sleep with Vivian, who he thought had a nice ass (one can only hope that it served her well). In his own autobiography he wrote he couldn't raid Olivier's "chicken coop," as "Larry was such a nice guy."

Well that was relatively good of him.

Vivian’s instability increased with time. He later recounted that "I would find Vivien sitting on the corner of the bed, wringing her hands and sobbing, in a state of grave distress; I would naturally try desperately to give her some comfort, but for some time she would be inconsolable." After a holiday with Noel Coward in Jamaica she seemed to have recovered, but Larry later recorded, "I am sure that ... [the doctors] must have taken some pains to tell me what was wrong with my wife; that her disease was called manic depression and what that meant—a possibly permanent cyclical to-and-fro between the depths of depression and wild, uncontrollable mania." He also recounted the years of problems he had experienced because of Vivian’s illness, writing, "throughout her possession by that uncannily evil monster, manic depression, with its deadly ever-tightening spirals, she retained her own individual canniness—an ability to disguise her true mental condition from almost all except me, for whom she could hardly be expected to take the trouble."

Larry directed his third Shakespeare film in September of 1954, “Richard III,” again playing the title role. He was joined by Cedric Hardwicke, Gielgud and Richardson, which led an American reviewer to dub it "An-All-Sir-Cast," nine years before ”It's a Mad Mad Mad Mad World (full disclosure... my dear sweet mother was an extra in the crowd scene at the end of this film) .”

“Of all the things I've done in life, directing a motion picture is the most beautiful. It's the most exciting and the nearest than an interpretive craftsman, such as an actor can possibly get to being a creator.”

The film was praised by the critics but didn’t make any money, which accounted for Larry’s subsequent failure to raise the funds for a planned film of “Macbeth," and Larry never directed another Shakespearean film after the "failure" of "Richard III."

However, he did win a BAFTA award for the role and was nominated for a Best Actor Academy Award.

Vivian became pregnant in 1956, and decided to stop working on Noel Coward’s comedy “South Sea Bubble." The day after her final performance in the play she miscarried and entered a period of depression that lasted for months.

That year Larry decided to direct and produce a film version of Terence Rattigan’s 1953 play, “The Sleeping Prince,” retitled “The Prince and the Showgirl (which I also had the pleasure of seeing on Larry’s birthday).” Instead of appearing with Vivian, he cast Marilyn Monroe as the showgirl, which during the production, he may have regretted.

In his autobiography Larry wrote that upon meeting Marilyn before they started making the film he was convinced he was going to fall in love with her. During production, he bore the brunt of her famous indiscipline and wound up despising her. However, he admits that she was wonderful in the movie, the best thing in it, her performance overshadowing his own, and that the final result was worth the aggravation. Here’s a clip.

Larry wrote this about Marilyn: “There were two entirely unrelated sides to Marilyn. You would not be far out if you described her as schizoid; the two people that she was could hardly have been more different. She was so adorable, so witty, such incredible fun and more physically attractive than anyone I could have imagined, apart from herself on the screen.” He called her a “A professional amateur.”

I’ll have to agree with Larry about Marilyn. She was a handful.

During the shoot, Larry, Marilyn, and her husband, the American playwright Arthur Miller ("Death of a Salesman,” “All My Sons,” “The Crucible”), went to see the English Stage Company's production of John Osborne's “Look Back in Anger” at the Royal Court.

At 50 years old Larry was suffering somewhat from a mid-life crisis, and needed, or wanted a change up in the direction of his personal and professional life.

“I had reached a stage in my life that I was getting profoundly sick of—not just tired—sick. Consequently the public were, likely enough, beginning to agree with me. My rhythm of work had become a bit deadly: a classical or semi-classical film; a play or two at Stratford, or a nine-month run in the West End, etc etc. I was going mad, desperately searching for something suddenly fresh and thrillingly exciting. What I felt to be my image was boring me to death."

Osborne was already at work on a new play, “The Entertainer,” concerning Archie Rice, a failing music-hall performer. Larry read the first act, which was all that had been written at the time, and asked to be cast in the part.

Larry’s biographer, Anthony Holden, maintained that Larry caught the two main aspects of Archie’s character, a brazen façade and a deep desolation, switching "from a gleefully tacky comic routine to moments of the most wrenching pathos."

The production shifted from the Royal Court to the Palace Theatre in September of 1957; after which it toured and returned to the Palace. The role of Archie's daughter Jean was played by three actresses during the various runs. The second of them was Joan Plowright, with whom Larry began an affair, that turned into a relationship, which turned into his third marriage, a marriage that would endure for the rest of his life.

Larry was nominated for a Tony Award as Best Actor (Dramatic) for "The Entertainer," in 1958. This was his only nomination for a Tony, an award he never won.

Larry was in good company as I’ve never won a Tony either, along with a rather large percentage of the world’s population.

Laurence received another BAFTA nomination for his supporting role in 1959's “The Devil's Disciple,” the film adaptation of Shaw’s play, which also starred Burt Lancaster and Kirk Douglas (as a matter of full disclosure, I’ve seen Kirk Douglas preparing food at the Los Angeles Mission here in downtown Los Angeles, as part of the mission’s Thanksgiving celebration. Never seen Michael though).

In 1960 he made his second appearance for the Royal Court company in Eugene Ionesco's absurdist play “Rhinoceros (full disclosure again. I once was the lead in Eugene’s “The Lesson,” and forgot my lines halfway through the show, and my leading lady, my girlfriend at the time, Michelle Meridian, slapped my fake mustache clean off my face during the play. This incident remains as one of the most embarrassing of my entire life, increased by the fact that the show was videotaped for examination at a later date).” The play was directed by Orson Welles, and it is said they didn’t see eye to eye on many things making the production a troubled one.

Larry’s and Vivian’s marriage by this time had run it’s course. In May of 1960 divorce proceedings began. Vivian reported this to the press and informed reporters of Larry’s relationship with Plowright, which is interesting considering her own history of infidelity.

Vivian named Joan Plowright --wife #3--as co-respondent in her divorce from Laurence, also on grounds of adultery.

The final decree was issued in December of 1960, which enabled him to marry Plowright in March of 1961. A son, Richard, was born in December of 1961; and two daughters followed, Tamsin Agnes Margaret, born in January of 1963, and Julie-Kate, born in July of 1966.

Larry appeared in two films in 1960. The first, filmed in 1959, was “Spartacus,” in which he portrayed the Roman general, Marcus Licinius Crassus, starring Kirk Douglas as Spartacus, Peter Ustinov (who won an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor), Jean Simmons, Charles Laughton, and Tony Curtis as Antoninus. The film won four Academy Awards in all. Here’s a clip.

It was directed by the young upstart Stanley Kubrick, the only film that he made in which he did not enjoy full artistic control.

The second was the film version of “The Entertainer.” The reviewer for The Guardian thought the performances were good, and wrote that Olivier "on the screen as on the stage, achieves the tour de force of bringing Archie Rice ... to life." Here’s a clip.

For his performance, Larry was nominated for another Academy Award for Best Actor.

He also made a television adaptation of Somerset Maugham’s “The Moon and Sixpence” in 1960, winning an Emmy Award.

1960 (February 8th) also saw Larry receiving a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame at 6319 Hollywood Blvd, right in front of the Sandy Burger Restaurant (which serves the best Korean burgers in L.A., possibly the only Korean burgers in L.A.).

He was originally cast in Burt Lancaster's role in Stanley Kramer‘s “Judgment at Nuremberg,” in 1961. If he had made that movie he would have worked with the American actor he admired most, Spencer Tracy.

My dear sweet mother worked with Spencer in “It's a Mad Mad Mad Mad World."

In 1961 Larry accepted the directorship of the new Chichester Festival Theater. For the opening season in 1962 he directed two neglected 17th-century English plays, John Fletcher's 1638 comedy “The Chances,” and John Ford's 1633 tragedy “The Broken Heart (the playwright would later go on to direct such American classics as “Stagecoach,” “The Searchers,” and “The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance,”)," followed by the old standby, “Uncle Vanya.”

The first two plays were politely received, but the Chekhov production attracted rave reviews. The Times commented, "It is doubtful if the Moscow Arts Theatre itself could improve on this production." High praise indeed.

Larry received yet another BAFTA nomination for his leading role as a schoolteacher accused of sexually molesting a student, Sarah Miles, in the 1962 film “Term of Trial," another of the films I was able to see during the TCM tribute.

In 1962 Larry turned down the role of Humbert in Stanley Kubrick’s “Lolita.” He originally agreed to do it for his former director, but dropped out on the advice of his agent.

Ironically, Stanley and Larry shared the same agent.

Back when the Chichester Festival Theatre opened, plans for the creation of the National Theatre were being made. The British government agreed to release funds for a new building on the South Bank of the Thames for said purpose. Larry accepted an invitation to be the company's first director. Pending the construction of the new theatre, the company was based at the Old Vic. With the agreement of both organizations, Olivier remained in overall charge of the Chichester Festival during the first three seasons of the National.

The first production of the National Theatre was “Hamlet” in October of 1963, starring Peter O'Toole and directed by Laurence.

Larry played "Othello" in 1964 at the National Theatre and his performance was widely acclaimed. It was during this time that he began to experience severe stage fright, which every performer experiences to a degree, but for some it can be paralyzing. He managed to carry on though, and last appeared on stage in 1974, in Trevor Griffiths "The Party," in which he delivered a 20-minute epilogue.

My favorite author, John Steinbeck, said that Olivier's 1964 turn as Othello at the National Theatre was the greatest performance he had ever seen. Larry would receive another Academy Award nomination for Best Actor two years later for the film version of this performance.

Larry spent over ten years as the director of the National (ultimately being pushed out by it’s governors over Larry’s insistence on producing a certain play). In his decade in charge he acted in thirteen plays and directed eight.

In 1966 Larry played the Mahdi, the "expected one of Mohammed," opposite Charlton Heston as General Charles Gordon, in the film “Khartoum,” a favorite of mine.

Here’s a 1966 interview with the film critic Kenneth Tynan, where Larry talked about acting.

In 1967 Larry began a long struggle against a succession of illnesses. He was treated for prostate cancer and, during rehearsals for his production of Chekhov's “Three Sisters,” he was hospitalized with pneumonia.

It was at this time he suffered the death of his former wife first hand.

In 1968 he appeared with Anthony Quinn, as the Soviet premier, in “The Shoes of the Fisherman.”

The next year he took on the heavy role of Edgar in a film version of August Strindberg's “The Dance of Death,” the finest of all his performances other than in Shakespeare, in John Gielgud's opinion.

He also appeared in two war films, portraying military leaders. He played Field Marshal French in the First World War film “Oh! What a Lovely War,” for which he won another BAFTA award, followed by Air Chief Marshal Hugh Dowding in “Battle of Britain."

On June 13th, 1970, Larry became the first actor to be made a peer of the realm (the only others subsequently being Bernard Miles in 1979 and Richard Attenborough in 1993) when Harold Wilson's second Labour government secured him a life peerage to represent the interests of the theater in the House of Lords. He was elevated to the peerage as Baron Olivier of Brighton.

As any fourth grader knows, a peerage is a legal system of largely hereditary titles in the United Kingdom, which is constituted by the ranks of British nobility and is part of the British honours system.

And in the United Kingdom, life peers are appointed members of the peerage whose titles cannot be inherited, in contrast to hereditary peers. Nowadays life peerages, always of the rank of baron, are created under the Life Peerages Act 1958 and entitle the holders to seats in the House of Lords, presuming they meet qualifications such as age and citizenship.

Baron Olivier’s health continued to deteriorate, as happens occasionally when people get older. In July of 1970, while playing Shylock in "The Merchant of Venice" at the National Theatre, the 63 year old was hospitalized with pleurisy (an inflammation of the pleura, the lining surrounding the lungs) and a thrombosis (the formation of a blood clot) of the right leg.

I really became aware of Mr Olivier’s presence and tremendous talent in 1972/1973, when I was around 18 years old, and when Larry took a leave of absence from the National to star with 39 year old Michael Caine in “Sleuth,” the Joseph L. Mankiewicz's film of Anthony Shaffer's play (when they met, Caine asked Olivier how he should address him. Olivier told him that it should be as "Lord Olivier", and added that now that that was settled he could call him "Larry"). Taking a rather modern and possibly biased look at the film today it’s easy to see the vehicle working much better as a play than a film as one of it’s main plot points doesn’t really hold up to close scrutiny. However, the entire cast of the film was nominated for Academy Awards (The film was the second to have its entire credited cast nominated for Academy Awards after “Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf” in 1966 and the first where all of the actors in the film were nominated (this feat has only been repeated once since when in 1975 the giant ant guy, James Whitmore was nominated for Best Actor in the film “Give 'em Hell, Harry!” Whitmore being the only member of the cast)), losing to Marlon Brando in “The Godfather,” another part that was originally offered to Larry, who perfected an Italian accent in order to play Don Vito Corleone, and who had been assigned the role. But just before filming began he fell ill and was replaced by Marlon. Here’s a clip.

Laurence won the Emmy Award for Outstanding Single Performance by an Actor in a Leading Role in 1973 for his portrayal of James Tyrone, Sr., in a television production of Eugene O'Neill’s whimsical masterpiece, “Long Day's Journey Into Night.”

In 1974 Larry appeared with Marilyn Monroe’s ex-husband (the pair had divorced in 1961. Nineteen months later she died after being poisoned with barbiturates administered to her by the CIA due to her involvement with John and Robert Kennedy), Arthur Miller, in as far as I know, his only film appearance in a sort of political documentary/ indictment of the Greek military junta of 1967 through 1974, in “The Rehearsal.”

In September 1974 he fell ill during a holiday in Italy with director Franco Zeffirelli (1968 film version of “Romeo and Juliet,” and which Larry narrated), and after x-rays and blood tests back in England at the Royal Sussex Hospital he was diagnosed with dermato-poly-myositis, a rare muscle disorder. For three months he remained critically ill in the hospital, and was told he could never act on stage again.

I’m not positive about when it was actually produced, but on March 6th of 1975 “Love Among the Ruins “ aired an ABC for the first time, starring Larry, along with everybody’s heartthrob, Katharine Hepburn., winning Emmy Awards for both for Outstanding Performance.

In early 1975 Larry was still recovering and regaining his strength due to the dermatomyositis. When strong enough producer Robert Evans offered him the role of the Nazi fugitive, Dr. Christian Szell (who was apparently a Nazi dentist, and I don’t have to tell you about the hell those guys raised), in 1976's “Marathon Man,” based on the book by William Goldman, who also wrote the screenplay, and starring Dustin Hoffman (who referred to Larry as “Sir," throughout the production) and shark boy Roy Scheider. Due to his health problems Larry was unable to secure the insurance that is normally required when hired for such a project. Evens, who had hired him to play Don Corleone a few years earlier, used him anyway.

“Is it safe?” Here’s a clip.

Larry was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Actor in a Supporting Role for his work, and won the Golden Globe in the same category.

1976 marks the year Laurence founded Academy Award Nomination Anonymous... a very exclusive 12 Step Program.

That year he also appeared with Alan Arkin, Vanessa Redgrave, and Robert Duvall, as an aggrieved Professor Moriarty in “The Seven Percent Solution.”

During this period of Larry’s life, due to his ill health and inability to secure major roles, and his desire to make as much money for his estate as possible while he still could, he took a lot of television work, including a couple of commercials for Polaroid cameras (although he insisted that they must never be shown in Britain). Here’s one from 1972.

In 1978 he appeared along with Gregory Peck in the film, “The Boys from Brazil,” playing the role of Ezra Lieberman, an ageing Nazi hunter. Peck played the Nazi, the very real historical Nazi serial killer, Dr. Josef Mengele (Full disclosure: I once helped Mr. Peck complete a long distance call from Los Angeles to Beijing when I worked for AT&T as a long distance operator... when they actually used people... which became bothersome for the company, so they discontinued the practice). Perhaps the real Mengele (An SS officer and physician in the Auschwitz concentration camp during World War II, who was notorious for selecting victims to be killed in the gas chambers, and for performing unscientific and deadly human experiments on the prisoners) saw the film as he was still alive at the time and living in a suburb of São Paulo, Brazil. The film opened in October of 1978 and Mengele didn’t die until February 7th, 1979, when he suffered a stroke while swimming at the beach and drowned.

Here’s clip that took several days to film due to Larry’s failing health.

Larry received his eleventh Academy Award nomination for this part, and although he didn’t win the Oscar, he was presented with an Honorary Award for his lifetime achievement.

The next year Larry appeared in the delightful romantic comedy, which I had the opportunity to see recently, “A Little Romance,” directed by George Roy Hill (“Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid,” “The Sting”), and co-starring "Hot Lips" Sally Kellerman, Arthur Hill, Thelonious Bernard, and a very young Diane Lane in her first film role. Here's a clip.

That year he also combated Count Dracula, as Professor Abraham van Helsing, along with Frank Langella, Kate Nelligan, and my favorite character actor, Halloween’s Dr. Loomis, Donald Pleasence. Here’s a clip.

Laurence continued working in film into the 1980s, with roles in “The Jazz Singer” (1980), “Inchon” (1981), “The Bounty” (1984) and “Wild Geese II” (1985)

He also continued to work in television; in 1981 he appeared as Lord Marchmain in “Brideshead Revisited,” winning yet another Emmy, and the following year he received his tenth and last BAFTA nomination in the television adaptation of John Mortimer's stage play “A Voyage Round My Father.”

In 1981 Larry was admitted to the Order of Merit, the first actor so honored in its entire 79-year-long history.

The Order of Merit recognizes distinguished service in the armed forces, science, art, literature, or for the promotion of culture. Admission into the order is the personal gift of the sovereign of the United Kingdom and the Commonwealth realms and is limited to 24 living recipients at one time from these countries plus a limited number of honorary members.

Seven years after Larry's death, John Gielgud was made a member of the Order, the second actor to be so honored.

In 1983 he played his last Shakespearean role as Lear in “King Lear,” for Granada Television, earning his fifth Emmy.

“... Lear is easy. He's like all of us, really: he's just a stupid old fart."

When the production was first shown on American television, the critic Steve Vineberg wrote:

“Olivier seems to have thrown away technique this time—his is a breathtakingly pure Lear. In his final speech, over Cordelia's lifeless body, he brings us so close to Lear's sorrow that we can hardly bear to watch, because we have seen the last Shakespearean hero Laurence Olivier will ever play. But what a finale! In this most sublime of plays, our greatest actor has given an indelible performance. Perhaps it would be most appropriate to express simple gratitude."

That same year he also appeared in a cameo alongside Gielgud and Richardson in “Wagner,” with Richard Burton in the title role.

Larry’s final screen appearance was as an old, wheelchair-bound soldier in Derek Jarman's 1989 film “War Requiem."

One of the 20th century's greatest orators, his last film had no dialogue, utilizing Benjamin Britten's musical piece of the same name throughout the entire movie.

Laurence did recite the poem "Strange Meeting" in the film's prologue, part of which follows below:

It seemed that out of battle I escaped

Down some profound dull tunnel, long since scooped

Through granites which titanic wars had groined.

Yet also there encumbered sleepers groaned,

Too fast in thought or death to be bestirred.

Then, as I probed them, one sprang up, and stared

With piteous recognition in fixed eyes,

Lifting distressful hands, as if to bless.

And by his smile, I knew that sullen hall,—

By his dead smile I knew we stood in Hell...

I am the enemy you killed, my friend.

I knew you in this dark: for so you frowned

Yesterday through me as you jabbed and killed.

I parried; but my hands were loath and cold.

Let us sleep now. . . .

Larry died of renal failure at 11:15 a.m., on July 11th, 1989 in his home near Steyning, West Sussex.

His cremation was held three days later, before a funeral in Poets' Corner of Westminster Abbey in October of that year. Joan Plowright and the three children of his last marriage were the chief mourners, along with Tarquin, Hester, and Olivier's first wife, Jill Esmond, in a wheelchair. Olivier's trophies were carried in a procession: Douglas Fairbanks Jr. carried the insignia of Olivier's Order of Merit, Michael Caine bore his Oscar for lifetime achievement, Maggie Smith a silver model of the Chichester theatre, Paul Scofield a silver model of the National, Derek Jacobi the crown worn in “Richard III,” Peter O'Toole the script used in “Hamlet,” Ian McKellen the laurel wreath worn in the stage production of "Coriolanus," Dorothy Tutin the crown worn for “King Lear,” and Frank Finlay the sword presented to Larry by John Gielgud, once worn by the 18-century actor Edmund Kean. Albert Finney read from Ecclesiastes: "To everything there is a season . . . A time to be born and a time to die". John Mills read from I Corinthians: "Though I speak with the tongues of men and angels . . . " Peggy Ashcroft read from John Milton's "Lycidas." Gielgud read "Death Be Not Proud" by John Donne. Alec Guinness gave an address in which he suggested that Olivier's greatness lay in a happy combination of imagination, physical magnetism, a commanding and appealing voice, an expressive eye, and danger: "Larry always carried the threat of danger with him; primarily as an actor but also, for all his charm, as a private man. There were times when it was wise to be wary of him." He reminded the audience that Laurence has been brought up as a High Anglican, and said he did not think the need for devotion or the mystery of things ever quite left him. The climax of the service was Larry’s own taped voice echoing round the abbey as he delivered the St. Crispin's Day speech from “The Chronicle History of King Henry the Fift with His Battell Fought at Agincourt in France.” Its quiet resolution was the choir singing "Fear no more the heat o' the sun" from "Cymbeline."

Larry received honorary doctorates from the university of Tufts, Massachusetts (1946), Oxford (1957) and Edinburgh (1964). He was also awarded the Danish Sonning Prize in 1966, the Gold Medallion of the Royal Swedish Academy of Letters, History and Antiquities in 1968; and the Albert Medal of the Royal Society of Arts in 1976.

For his work in films, he received four Academy Awards: an honorary award for “Henry V,” a Best Actor award and one as producer for “Hamlet,” and a second honorary award to recognize his lifetime of contribution to the art of film.

He was nominated for nine other acting Oscars and one each for production and direction. He also won two British Academy Film Awards out of ten nominations, five Emmy Awards out of nine nominations, and three Golden Globe Awards out of six nominations, and he was nominated once for a Tony Award.

In addition to the naming of the National Theatre's largest auditorium in Larry's honor, he is commemorated in the Laurence Olivier Awards, bestowed annually since 1984 by the Society of West End Theatre.

In 1991 John Gielgud unveiled a memorial stone commemorating Olivier in Poets' Corner at Westminster Abbey, where his memorial was held.

In 2007, the 100th anniversary of Larry’s birth, a life-sized statue of him was unveiled on the South Bank, outside the National Theatre; the same year the British Film Institute held a retrospective season of his film work.

And I watched “The Entertainer,” this morning at about 4:00AM.

Here’s a link to Larry’s Official Website.

And finally, Baron Olivier’s name in Elvish is Olwë Táralóm, as Larry or Fëanáro Táralóm as Laurence.

I wish to apologise for the length of time between parts 1 & 2, but computer’s had to be switched out, and a whole host of other technical problems surmounted before I could continue, and my resources are few and pitiful.

In any case Joyce’s Take rejoices in the opportunity to recount and remember a small portion of the life of this remarkable man and actor.

Happy birthday Larry!

No comments:

Post a Comment